- Home

- The Universe

- Human Origins

- The first ape men

- Proconsul

- Nakalipithecus

- Chororapithecus

- Sahelanthropus

- Orrorin Tugenensis

- Ardipithecus Kadabba

- Paranthropus aethiopicus

- Australopithecus Anamensis

- Ardipithecus Ramidus

- Australopithecus Afarensis

- Australopithecus Africanus

- Australopithecus sediba

- Paranthropus boisei

- Paranthropus robustus

- Kenyanthropus platyops

- Australopithecus garhi

- Stone age cultures & technologies

- Stone Age ancestors

- Out of Africa Migration

- The first ape men

- Civilisation

- Peoples & Cultures

- Interactive Exhibitions

- Museums of Kenya

Highland Nilotes

Highland Nilotes generally settled in the highland areas of the Rift Valley and Western Kenya, and practice pastoralism and agriculture.

The Kalenjin languages in Kenya are a group of twelve related Southern Nilotic languages spoken in Kenya, eastern Uganda and northern Tanzania. During their settlement in the Mt Elgon area, people who are today known as the Kalenjin called themselves Miot, Mmyoot or Mnyoot. When they migrated to their present homes, they adopted or were given new names by which they are now known separately.The term Kalenjin comes from a Nandi expression meaning ‘I say (to you)’. Kalenjin in this broad linguistic sense should not be confused with Kalenjin as a term for the common identity the Nandi-speaking peoples of Kenya assumed halfway the twentieth century. The name “Kalenjin” comes from a popular 1940s radio show hosted by a member of one of these tribes, who would begin his show each week with the expression “Kalenjin” meaning Let me tell you…In the late 1940s and 1950s, several Nandi-speaking peoples united to assume the common name “Kalenjin”.

The Kalenjin languages are generally distinguished into four branches, based on Ethnologue 16 of 2009:

Spoken in the Mount Elgon area in western Kenyan and eastern Uganda. There are two main languages:

• Kupsabiny

• Sabaot: a name assumed by various related peoples including the Kony, Pok, and Bong’om (after whom the Western Kenya town of Bungoma is named)

• Kipsigis, • Terik, • Markweta, • Nandi, • Keiyo, • Tugen

The cluster also includes other Tanzanian “Ndorobo” speakers such as Kisankasa, Aramanik, Mediak and Mosiro. Ndorobo is a term considered derogatory, occasionally used to refer to various groups of hunter-gatherers in this area, including the Ogiek.

A language cluster of the Kalenjin family spoken or once spoken by the Ogiek peoples, who are scattered groups of hunter-gatherers in Southern Kenya and Northern Tanzania. Most if not all Ogiek speakers have assimilated to cultures of surrounding peoples: the Akiek in northern Tanzania now speak Maasai and the Akiek of Kinare, Kenya now speak Gikuyu. Ndorobo is a term considered derogatory, occasionally used to refer to various groups of hunter-gatherers in this area, including the Ogiek.

Also known as Pokot, Päkot, Pökot and in older literature as Suk. Speakers are found in Western Kenyan, Eastern Uganda and Northern Tanzania.

The following table contains more detailed descriptions of some of the cultures.

Language: Keiyo. Alternate names: Elgeyo, Keyo. Keiyo is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

The Keiyo. They were earlier known as Elgeyo (“El-gay-o”), a Maasai term.

Until recently the Keiyo people were known as Elgeiyo which was a corruption of the term Keiyo which means “for or from Keiyo land”.

The Keiyo are part of the Kalenjin sub-tribe i.e. the ‘Mnyoot’ who remained in the Kerio Valley when other Kalenjin communities moved to their present homelands.

Until the early 1950s the Kenyan people now known as the Kalenjin did not have a common name; they were usually referred to as the ‘Nandi-speaking tribes’ by scholars and administration officials alike. In the late 1940s and the early 1950s, several Nandi-speaking peoples united to assume the common name ‘Kalenjin’, a Nandi expression meaning I say (to you).

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Nandi-Markweta, Nandi.

Origins of the community: The origin of the Keiyo people is relayed through oral traditions. As part of the Kalenjin ethnic group, they trace their origin to a forefather known as Kole, who lived around Mt Elgon (i.e. Tolwop Kony). After moving southwards along wide valleys and a wide river (believed to be the Rive Nile), Kole had five sons. The first born, named Chemng’olin, moved from their homeland with the aim of ‘kondi’ i.e. to inherit and conquer. The second son preferred the task of reproduction-Kosigis-meaning to “reproduce”. This is the Kipsigis sub-tribe.

The third son wanted to practice milking and hence bore the name Keisyo, later referred to the Keiyo. The fourth son wanted to collect termites as there was severe drought then. The process of collecting termites entailed the poking (‘ketugen’) of the ground for the termites to come out of the ground. Upon leaving his homeland he said he is going ‘this side’ (kamase) and hence the present Kamasia or the Tugen. The fifth son chose to remain in the ancestral homeland, and stay Kong-kony meaning ‘to stay rooted’.

The first two sons followed the westerly direction along Lake Victoria, while the third and fourth sons followed the eastern direction, through the Cherang’any hills into the valley southwards along the Kerio River (Endo) to their present location.

Each of them begot offspring through assimilation and reproduction which led to the Nyang’ori/Terik & Ogiek for the first and second sons, the Marakwet and Pokot (Suk)/Njemps/Tchamus) for the third and fourth sons respectively. The last son is associated with the emergence of the Sabaot, Pok and Bagomek.

The Keiyo probably settled in their current land not more than 300 years ago, and basically found the land inhabited by the hunting and gathering community, the Kapchegrot and the Kurut, who were driven out of the land by an invasion of locusts and flooding which drove them out of the caves they had hidden in along the Endo Valley. They returned later, only to find their land already inhabited.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Keiyo number 313,925.

According to SIL Ethnologue the population count for the Keiyo stood at 111,000 in 2007.

Population figures released in January 2007 estimated the population of Kenya to be 36,914,721. Of that 12% are thought to be Kalenjin, approximately 4.4 million people. Collectively the Kalenjin comprise Kenya’s fourth-largest ethnic group, with the Keiyo numbering about 144,000 people.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Keiyo settled in Rift Valley Province’s Elgeyo Marakwet district.

The Keiyo live near Eldoret, Kenya in the highlands of the Keiyo district.

The administrative location of the Keiyo community is Keiyo district which was recently hived off from the former Elgeyo Marakwet district. The neighbouring districts are: Baringo to the east, Marakwet to the north and Uas Nkishu to the west. The narrow strip of the country occupied by the Keiyo stretches from Tugumoi at the southern end to Kendur in the north where it borders Marakwet. The Elgeyo escarpment is the major divider of the two contrasting geographical zones in the district – the highlands and the valley. The altitude drops from over 2,500m in the highlands to 1,300m on the Kerio Valley floor.

Housing: Traditionally, the Kalenjin built round homes of sticks and mud plaster, with pointed thatch roofs with a pole out the centre.

Economic activities: They subsist mainly on grain; and the milk, blood and meat provided by their cattle. They moved away from the eastern grazing lands of the Great Rift Valley during the expansion of the Maasai tribe. The loss of much of their grazing land forced them to reduce their herds and rely more on agriculture.

Cycles of life

Birth: A woman was always married after the confirmation that she had conceived. Expectant mothers were fed with buffalo’s meat and grain meal made of millet and sorghum. She took milk from a selected cow. Two months before giving birth she was relieved from all her duties and a young girl was assigned the responsibility of looking after her, eventually she was rewarded with wire ornaments. Near birth, two midwives were identified and a gourd placed near the door to show visitors that a woman was expectant in the homestead.

After birth, the child was washed and after inspection of the mouth the child was left unwashed for the next two days after which the child was washed daily with water boiled with some herbs. Mother and child were to stay in seclusion for a minimum of two weeks during famine to six weeks on normal times as the woman was considered unclean. Before the woman breaks the seclusion, she makes beer and cooks food for a celebration in which old women are invited. After this she is escorted outside the house.

Naming: Traditionally, names for males begin with the prefix “Ki” while those for females begin with “Che” or “Je”. The names refer to some circumstance when the child was born. For example: Kipchoge (a boy born near the granary), Kibet (a boy born during the day), Cherutich (a girl born as the cows were coming back home), and Jepkemoi (a girl born at night).

A woman who had had a succession of losses was allowed to leave the village immediately after birth of the child, taking particular interest when crossing the river. She would then return after sometime and on giving birth to another child he/she would be given a special name “Aiyebei” indicating that a river was crossed, “Tegerio” or “Sirma” to indicate sole survivor. The child would be named after an animal like a hyena to deceive the spirits responsible for previous misfortune. Two years after the birth of such a child, elders would assemble and beer blown over a leopard footprints refered as “seiya”. A cowrie shell was then pierced and suspended on the child’s neck which was later replaced with a metallic wire from the mother’s relatives the placed on the neck or the left arm on a boy. This charm would not be discarded in one’s lifetime. The mother of the child was required to wear an amulet from an ant bear hide on her neck the next time she is expectant.

A child was first named after the season or the time the child was born e.g. Chebigo to signify evening, Kibiwot or Chebiwot on rainy season. Jerop or Kiprop when its raining, Kiptoo when there are visitors. Later an elaborate naming ceremony was conducted with four or five old men and women after the seclusion of the mother and child. Beer was passed over after the tobacco snuff was blown near the child. Names of deceased relatives were called, males names if a boy and female names if a girl. If the child sneezed when the name was called out he/she would take the name, unless he/she gets sick. This would result in another naming ceremony.

Education: Girls were taught to kneel in front of men and were not allowed to speak to men until they had been circumcised. Girls were taught how to make gourds and pots for carrying water. They learned to carry firewood and look for wild vegetables. Boys were taught to care for the cattle and the boma (cattle shed). Boys were not allowed to sleep in the same house with their mother after the age of 5.

Initiation: Pending circumcision, the youth are not only barred from marrying, but also any form of attachment with girls is highly punishable and outlawed. The circumcision ceremony was not done annually as it is done presently. It was done at certain times regulated by constellation aqua. There were special names of reference for those circumcised together. For men, they called each other ‘Bakule’ and ‘Bosoi’ for women.

Language: Kipsigis. Alternate names: Kipsiikis, Kipsikis, Kipsikiis. Kipsigis is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Nandi-Markweta, Kipsigis.

Origins of the community: The Kipsigis are a sub-group of the Kalenjin and originated in the Sudan, and moved into the Kenyan area in the 18th century. The Kipsigis are part of the Highland Nilotes group of people.

Kipsigis woman earrings called Syepanik at Hyrax Hil Museum.

The Kipsigis community is an amalgam of people from many other communities. Dr Toweett wrote that the people who call themselves Kipsigis are in no way a hundred percent Kipsigis. As a tribe the Kipsigis is not a pure blood. The designation “Kipsikis or Kipsigis” includes persons of foreign extraction such as the Terik, the Nandi, the Keiyo, the Maasai, the Dorobo, the Tugen (Kamasia) and the Kisii.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Kipsigis number 1,916,317. The Kipsigis are the most numerous tribe of the Kalenjin in Kenya. The last census put their number at 1.972 million speakers, accounting for 45% of all the Kalenjin speaking people.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Kipsigis settled on the the highlands of Kericho stretching from Timboroa to Mara River in the south, the west of Mau Escarpment in the east to Kebeneti in the west. They also occupy, parts of Laikipia, Kitale, Nakuru, Narok, Trans Mara District, Eldoret and Nandi Hills.

After their last migration, the Kipsigis settled in Rift Valley Province’s Uasin Gishu district and Nandi district.

Kipsigis is spoken mainly in the Kericho district of the Rift Valley Province. The Kipsigis territory is bordered to the south and south-east by the Maasai. To the east, Gusii (a Bantu language) is spoken. To the north-east, other Kalenjin people are found, mainly the Nandi. East from the Kipsigis, in the Mau forests, live some Okiek speaking tribes.

At first the Kipsigis lived at the foot of the Nandi hill close to their “blood” brothers, the Nandi at Kedowa, Fort-Ternan (Chilchila) Kibigori and Muhoroni, concentrating in the southern parts of these places and also in Tulwap and Binyiny. They then moved to the Chemosit river and as far as Tergat near the present Kericho town. All the country around Mau hills is known to the Kipsigis as Tegat (Bamboo) because it had thick bamboo forest. The Kipsigis lived in Tegat for many years and there they interacted with the Ogiek.

Housing: A typical Kipsigis homestead of traditional design contains a number of structures and labelled spatial features. Ko (or kot in the definite term) can be used to refer to various buildings, but most generally to the largest structure e.g. kot ap mosop, the house built for each married woman. A few yards outside the door of the kot ap mosop is the mabwaita, a sheaf of tall thin branches tied around a post in the ground. Mabwaita can be glossed as “the family altar”. It is renewed with fronds from several sacred plants at ceremonies involving family members, and becomes the focal point of many domestic ritual activities.

Associated with most houses is a granary (choget), or a combined goat house and storage shed. Women maintain a small fenced garden (kabungut) close to their houses where they grow a variety of greens and calabashes.

The kot ap mosop is a round mud hut with a thatch roof. Each of the scores of separate pieces and furnishings has its own name, and many are associated with the particular statuses and activities of the occupants. For example, the apex of the roof, kimonjogut, a wooden post sticking up like a lightning rod, often carved in geometric patterns, represents the man of the house and is removed upon his death.

Most traditional Kipsigis houses consisted of one circular room undivided by interior walls. Essentially this room serves as a married woman’s bedroom, kitchen, and nursery. The door is always located on the downhill side of the house, though never directly on the east-west axis, and the man’s bed is on the western side of the room. On the eastern side of the doorway inside the room is the area known as injor. This is where the woman’s bed where infants and toddlers sleep with their mothers while older pre-adolescent children sleep on a skin on the floor next to her bed.

A Kipsigis homestead generally has three house types: a father’s house, rectangular in design often covered with corrugated tin roof; a kitchen building, which is round, with a thatched roof, where children and unmarried daughters sleep; and a bachelors’ house, where initiated young men sleep. Most Kipsigis houses are of mud-and-wattle construction; however some prosperous farmers are now building stone houses that incorporate various features of European design.

Economic activities: The Kipsigis are traditionally pastoralists but today they live both as farmers and pastoralists. They are famously known for growing tea.

Maize has largely replaced finger millet and sorghum as the staple food, although the latter are grown on small plots for home consumption. Maize is also grown as a cash crop. At higher elevations, where soil conditions and rainfall are favourable, most farmers grow tea on plots that generally range between 0.2 and 2.4 hectares. Green leaf is plucked throughout the year and sold to state-run factories, where it is processed.

Cycles of life

Initiation: Men undergo circumcision at an average age of 14 years. Traditionally, boys were housed in a ‘menjo’ next to a forest, or away from homesteads and fed there as they await their genitals to heal. Female circumcision used to be practised but is currently losing ground to Christian beliefs and government legislation.

Boys return from initiation with an ascetic (strict) bearing that signifies their ascent from childish things and childish behaviour. They are expected to remain aloof from their mothers and sisters, who in turn treat them with respect. Girls return from initiation with the expectation they will soon be married, a situation that is often forestalled these days by their continuing education.

Marriage: Bride-wealth payments include livestock and cash. Every married woman keeps her own house, in which the cooking is done and young children sleep.

Death: The Kipsigis bury their dead quickly. The eldest son will bury his father, and the youngest son will bury his mother. After a death, the immediate family will retreat from public life to mourn. The spirit of the recently deceased patrilineal relative is believed to be reincarnated in a newborn child.

Language: Markweeta. Alternate names: Endo, Endo-Marakwet, Marakuet. Markweeta is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

The name “Marakwet” is a corruption of Markweta -one of the sub-sibs (“sib” means related by blood;akin) which inhabit the territory including the Endo, Almo, Kiptani and Cherang’any (or Sengwer).

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Nandi-Markweta, Markweta.

Marakwet food container called Ketub, made from local trees.

Origins of the community: By the 19th century, all people now known as Kalenjin (Mmyoot) lived within 100miles (160 kilometres) of the place known today as Eldoret town. It is not easy to give a coherent and identical account of how the less politically united Marakwet groups came to be formed and settled in the areas they live in today. According to B.E. Kipkorir and F.B. Welbourne, the Talai in North Marakwet aver (assert or affirm with confidence) that according to their traditions they came from Misoi and that an important stopping point en route was at Mt Elgon. The Sogom in Marakwet say that they came from Misri but did not go to Mt Elgon, instead, they came through Turkana.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Marakwet number 180,149. According to SIL Ethnologue the population count for the Marakwet stood at 161,000 1997.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Marakwet settled in Rift Valley Province’s Elgeyo Marakwet district.

The Marakwet predominantly live in Marakwet district in the North Rift Valley Province of Kenya. Others live in Trans Nzoia East and Uasin Gishu North districts and indeed in other towns across the country.

The territory occupied by the Markweeta is known administratively as Marakwet. It is bounded (limit or boundary) on the east by the Kerio River at 3,500feet (966m), which runs through some parts of the Great Rift Valley. To the west it includes almost the whole of the Elgeyo Escarpment. Shaded to the east by the Kamasia Hills, the Kerio Valley is generally dry; like most of the Rift Valley, its floor is rough and arid; and, as it extends northwards, it gradually becomes desert. That part of the valley which lies in Marakwet is extremely fertile when irrigated, but subject to considerable erosion.

Housing: Kerio Valley is infested by mosquitoes and tsetse-flies, and provides a ready highway, from north to south for potential raiders. In defence, therefore, against man and disease, the Marakwet traditionally built their houses on the escarpment which rises 4,000 feet (about 1200m) to the west.

Economic activities: They practice mixed small-scale farming and keep dairy cows, sheep, and chicken. They grow mostly maize, potatoes, beans and vegetables in the highlands. Those who live along the escarpment and the Kerio Valley keep mostly goats and beef zebu cows and grow millet, sorghum, cassava, vegetables and fruits especially mangoes and oranges.

Goats, remain the most common animal kept by the Marakwet, as they are well adapted to life on the steep slopes of the Cherang’any. The Marakwet live on the steep slopes of the hills rising from the floor of the Kerio Valley where they build terraces villages cut into the sides of the hills.

Crops are grown in the valley, which is irrigated through man-made furrows, perhaps four hundred years old, running from the Arror, Embobut and Embomon Rivers. There is considerable bee-farming especially among the Cherang’any. The valley inhabitants tend ant-hills which, at the beginning of each rainy season, yield vast numbers of flying ants, a great delicacy among the Marakwet and Tugen.

Cycles of Life

Initiation: Initiation was the only way by which both males and females could become adult members of the society. Initiation into a particular age-set was held in three sub-sets, separated by a year. The senior sub-set was known as chongen, while the junior two were called aiberi. There was a period of seven years or more before initiation began into the next set.

In the 20th century, the age of initiation was considerable for both males and females. Traditionally, boys would grow beards and go to war before they were initiated, while girls were probably initiated between the ages of sixteen and twenty-one. From 1964, boys were to be initiated at eighteen and girls at fourteen.

Language: Pökoot. Alternate names: Pakot, Pökot, Suk. Pökoot is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

Pökoot language is classified as the northern branch of the Kalenjin languages found in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

The Pökoot are usually called Kimukon by the other Kalenjin peoples.

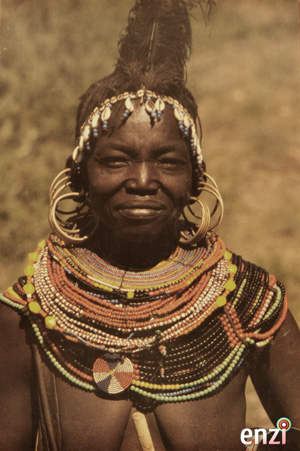

Pokot woman

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Pokot.

Origins of the community: The Pokot people are a sub-tribe of the Mmyoot (Kalenjin) tribe who are said to have been the first to leave Tulwop Kony (Mount Elgon) cradle-land for the area they now live. Until 1922, the Pokot country which lay west of the Suam River was in Uganda. In that year the territorial boundary was adjusted.

Many Pokot people from the present eastern part of the Pokot area claim that they come from the hilly areas of northern Cherangani. Halfway through the 19th century, they seem to have expanded their territory rapidly into the lowlands of the Kenyan Rift Valley, mainly at the expense of the Laikipia Maasai people.

The Pökoot were once considered part of the Kalenjin people who were highland Nilotic people who originated in southern Ethiopia and migrated southward into Kenya as early as 2,000 years ago

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Pokot number 632,557.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Pökoot settled in Rift Valley Province’s Baringo and West Pokot districts.

The Pokot live in West Pokot and Baringo districts of Kenya and in eastern Karamoja in Uganda.

The Pökoot area is bordered to the north by the Eastern Nilotic language Karimojong. Turkana, another Eastern Nilotic language, is found to the north-east. To the east, the Maa languages Samburu and Camus (on Lake Baringo) are spoken, and to the south, the other Kalenjin languages Tugen and Markweta are found, which show considerable influence from Pökoot.

Housing: The agricultural Pökoot live in sprawling “villages” made up of 50 or more homesteads which may be as much as 2 miles apart. Two or three “villages” make up a “federation”. Villages and federations have a council of elders who settle disputes and allocate irrigation waters. The semi-pastoral Pökoot live in settlements scattered across the plains. Each settlement consists of an extended family group with the eldest man serving as the leader.

Economic activities: Based on areal (a geographical region, tract) and cultural differences, the Pokot people can be divided into two groups: the Hill Pokot and the Plains Pokot. The Hill Pokot live in the rainy highlands in the west and in the central south of the Pokot area and are both farmers and pastoralists. The Plains Pokot live in the dry and infertile plains, herding cows, goats and sheep.

Those who are cultivators mainly grow maize. Nevertheless, whether a pastoralist or a farmer, wealth among the Pokot is measured by the number of cattle one has. Cattle are mainly used to pay bride price and for barter trade.

Dairy products like milk are an important part of the diet of the Pokot. Porridge made from wild fruits boiled with a mixture of milk and blood, makes a meal rich in iron and other nutrients is the staple of the Pokot diet.

Though the Pökoot consider themselves to be one people, they are basically divided into two sub-groups based on livelihood. About half of the Pökoot are semi-nomadic, semi-pastoralists who live in the lowlands west and north of Kapenguria and throughout Kacheliba Division and Nginyang Division, Baringo District. These people herd cattle, sheep and goats and live off the products of their stock. The other half of the Pökoot are agriculturalists who live anywhere conditions allow farming.

Some Pökoot keep bees for production of honey and honey wine which is important in certain ceremonies. They also do some hunting, but not really as a means of subsistence. More and more Pökoot are turning to panning gold part-time.

Millet and eleusine (finger millet) were the major traditional crops before maize was introduced. They also grew some tobacco to trade with the Turkana for sheep and goats.

Cycles of life

Birth: When an expectant woman is due to deliver she returns to her matrimonial home where she gives birth and recuperates. However, not all women do this. The mother and the newborn remain in seclusion for a period of time to protect them from people with ‘bad eyes’. The child’s father slaughters a goat for the mother and to celebrate the birth. He keeps away from his wife for a while. Mother and child wear special protective charms immediately after birth.

Naming: A child is named immediately after birth. The child’s immediate name is got from the season, for example Krop and Cherop are given to a boy and girl respectively born during the rainy season, Kimei for a child born in the dry season. Children are also named after their ancestors as well as according to prevailing circumstances e.g. Poryot is the name given to a child born during times of war.

Initiation: One is initiated into the age-set through the circumcision ceremony which occurs at 10 to 15 year intervals. There are 8 age-sets in a cyclic age-set system. Each age-set has its own responsibilities with more authority wielded by the older age-sets. Elders (of the eldest age-set) sit in the centre of the traditional half circle (kirket) during ceremonies.

Marriage: In traditional Pokot culture, young girls around the age of twelve are married off to older men after having gone through a female circumcision rite that ushers them into “adulthood”.

Marriage occurs between young “warriors” of 20 to 25 years of age and the newly circumcised girls of 14 or 15 years of age. Girls must be circumcised before getting married or giving birth.

Language: Sabaot. Alternate names: “Mt Elgon Maasai”, Sebei. Sabaot is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Elgon.

Origins of the community: The Sabaot tribe are one of the nine sub-tribes of the Kalenjin ethnic group. They are commonly referred to as “Kapkugo” by the other Kalenjin sub-tribes. Their history of immigration dates back to the spread of the Kalenjin people over a thousand years from a place called Misri in the north to Kitale plateau, Sebei and Bungoma districts. They are the original inhabitants of the region they occupy today. Before colonisation, the pastoralist Sabaots roamed the whole of Trans Nzoia and Mount Elgon region. At the onset of colonialism their land was alienated by the white settlers and they were expelled and dispersed to Uganda, Pokot, Maasailand and Tanzania. This dispersion deprived the Sabaot community of their only form of livelihood – pastoralism.

During the colonial era, other communities, notably, the Bukusu, moved into Trans Nzoia to work in the settler farms. After independence, many of the communities squatting in settler farms bought land in Trans Nzoia and established settlement schemes there, without taking into account the indigenous land rights of the Sabaot community.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Sabaot number 240,886.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Sabaot settled in Western Province’s Mount Elgon District; and Rift Valley Province’s Trans Nzoia District.

The Sabaot people settled on or near the slopes of Mount Elgon. The hills of their homeland gradually rise from an elevation of 5,000 to 14,000 feet. The area is criss-crossed by numerous mountain streams and waterfalls. Mount Elgon is an extinct volcano about 50 miles in diameter. The Kenya-Uganda border goes straight through the mountain-top, cutting the Sabaot homeland into two halves.

The mainland formation in the region is geographically influenced by Mount Elgon which slopes gently through the area with a terrain that rises from 1,800m above sea level to about 4310m. The region’s annual rainfall ranges from 1,400mm to over 1,800mm per annum and is fairly distributed. Temperature varies between 14°C and 24°C.

Majority of the Sabaot people live in Mount Elgon district in Western Province of Kenya which is located on the south-eastern slopes of Mount Elgon bordering Bungoma district to the south, Trans Nzoia to the east, and Uganda to the west. There is undocumented significant population of Sabaots living in Saboti in Trans Nzoia disrict, Endebes in Kwanza district, the central region of Bungoma district (Bong’omek), Tanzania, Sudan, Uganda and other African countries. Housing

Economic activities: Traditionally, the Sabaot people were cattle herders, however, in recent times they have turned to growing maize and vegetables owing to scarcity of land.

The Sabaots raise cattle, goats and sheep; and plant the following crops – maize, millet, potatoes, beans, bananas, sunflower, coffee, tea, pyrethrum, wheat, tomatoes, cabbages, sukuma wiki (kale) sweet potatoes and onions.

Cycles of life

Naming: During a naming ceremony, the child was given names based on a variety of factors such as: time of birth, skin pigmentation, place of birth, special events evolving during birth, past relatives, weather. Children also acquired other names as they grew based on special skills or unique attributes they possessed.

Initiation: Between the ages of 14-25 young men are initiated with words through an instructional lesson on how to look after cattle, care for the household, build a house, and how to relate to others in the family and community. When the young man is able to do this things independently, he can request for circumcision from the father. If the latter obliges, then the young man goes through the circumcision rite of passage, after which he will be considered an adult. However, he will not be considered as having reached manhood until he’s married and established his own home and has children.

Girls are circumcised between the ages of 16 and 25. The girls were circumcised just after dawn, at a ceremony where customarily only females were in attendance -the initiates, their female relatives, and other women and girls. The initiates were made to lie down with their arms above their heads and their legs spread. They were not supposed to be tied of held during the operation.

Just before circumcision, the intestines of a sheep which had been slaughtered for the occasion were laid on the face of the girls to keep their eyes open during the operation. Then the circumciser (surgeon) would make three separate incisions into each girl. Thereafter, the girls were led into a fenced boma across the entrance of which the entrails of the slaughtered sheep were laid. Two spears were placed on each side of the entrance pointing outwards from the boma, only leaving enough space for one person to enter. The slaughtered sheep and the spears were to scare away evil spirits. Once the girls were inside the boma, people were allowed to visit them. About one hour after the ceremony, the initiates were led away to the huts and put in the care of old women until they recovered in one or two months’ time. The wounds were treated with urine. After recovery, the girls were regarded ripe and eligible for marriage, and they could enjoy other privileges accorded to women.

Language: Terik. Alternate names: Nyang’ori. Terik is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

Terik is classified as an endangered language. This is because its speakers have become assimilated into the dominant Nandi community and adapted the Nandi language. About 50,000 Terik (less than half of the total population) still speak the Terik dialect, but all are middle-aged or older. Most children grow up using Nandi.

The Terik language is in a process of being replaced by Nandi, whose ethnic group influenced the social structure of the Terik people as well as their language. This process started in the 1920s and is likely to lead to the complete disappearance of Terik as a distinct linguistic form. The closer a Terik lives to the Nandi territory, the less likely he or she is to be a ‘mixed speaker’ and the more likely to be a ‘Nandi-ized speaker’.

The Luo refer to them as nyangóóri, but the Terik consider this a derogatory term. The Terik call themselves Terikeek; in their usage, ‘Terik’ refers to language, land and culture.

The nickname ‘nyang’ori’ was derived from the Luo community, because the Terik, being pastoralists used to invade the Luo areas for pasture during the drought seasons of yonder. On the way back home, the Terik would bring with them cow peas, a crop known as “ngor”. Hence the name Nyang’ori was derived from the word “ngor” literally meaning ‘the people of the cow peas’.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Nandi-Markweta, Terik.

Origins of the community: According to their oral history, the Terik are “people of Mount Elgon”. This is confirmed by linguistic as well as by Bong’om traditions that “the people who later called themselves Terik were still Bong’om when they left Elgon and moved away in a southern direction”. In pre-colonial times, relations between the Terik and the Nandi (their eastern neighbours) were characterised by mutual raids for cattle, land and women; however, the relationship has thawed somewhat in recent years.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Terik number 300,741.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Terik settled in the Rift Valley Province’s Uasin Gishu district; and Nandi district.

The Terik people are a Kalenjin group inhabiting parts of the Kakamega and Nandi districts of western Kenya. They live wedged in between the Nandi, Luo, and Luhya (Luyia) peoples.

The Terik are a Kalenjin-speaking group residing mainly in Aldai Division of Nandi South district. Before they were administratively placed under the greater Nandi district in 1963, after Kenya’s independence, the colonial government administered Terik under the then Kakamega district in Western Province.

Language: Tugen. Alternate names: North Tuken, Tuken.

Tugen is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin. They are a branch of the Kalenjin community.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Nandi-Markweta, Nandi.

Origins of the community: The Tugen patriclans, whose major names are the same as those of the neighbouring Keiyo, Marakwet and Nandi, came from two directions. Most of them came from the Mount Elgon area where they lived with or near Kalenjin speaking Kony people. Others came from the direction of Mount Kenya (Koilegen) and a few are said to have spoken Maasai when they arrived.

The Tugen, known in extant literature as the Kamasia, trace the majority of their clans to three major sources. The largest group of clans, particularly among the Arror, claim origin from Sumo, or the Mount Elgon areas. B.K. Kipkulei, who has studied them, claims that most of the groups that claim Sumo origin arrived in their present country before AD 1800. One migrant group from Sumo, the Kaborios, travelled to Tugen country via Tambach, settling for a while at Ngolong. They later migrated to their present home around Kabartonjo area, where they found other clans already settled.

Tugen oral traditions indicate three possible areas of origin: north-west and east of their present habitation. One group came from Sumo (the area to the west between Mount Elgon and Cherangany hills). Sumo is a Kalenjin territory from which the biggest bulk of the Tugen emanated. The second and third groups migrated from Suguta (Lake Turkana in the north) and Koilegen (the area to the east of the Tugen Hills) respectively. The second and third areas of origin brought with them a group (some were of Turkana and Maasai origins) of non-Kalenjin speaking people from northern Kenya and the highlands to the east of the Rift Valley respectively. As the Tugen moved, they encountered these communities on their way which they assimilated.

Population : According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Tugen number 109,906.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Tugen settled in Baringo district north of Nakuru town.

The Tugen occupy the districts of Baringo and Koibatek in Kenya’s Rift Valley Province. They are further subdivided into four sub-groups:

• Arror live in the Highlands of Kabartonjo and the lowlands of Kerio Valley (Barwessa) and Lake Baringo of North Baringo District.

• Samors who live in the wider Kabarnet in Central Baringo District

• Lembus live in the farmlands of Koibatek District

• Endorois who live in the lowlands of Koibatek District

The Tugen ancestral home is in the present Baringo and Koibatek districts in the Rift Valley Province. Some of them have migrated and settled in the neighbouring districts of Nakuru, Uas Nkishu and Laikipia. The Tugen are not the only inhabitants of Baringo and Koibatek districts; the other inhabitants include – the Pokot, Kipsigis, Jemps (Chamus or Il Tiumus) and Agikuyu.

The Tugen country is situated between the Elgeyo escarpment to the east and Ngelesha hills to the west and the Equator touches its southern boundary. To the west lies Kerio Valley where the River Kerio flows along the Valley floor marking a natural boundary between Baringo and Keiyo and Marakwet districts. To the east the land rises sharply from 3,500feet (2,440m) at the Tugen Hills. The land inhabited by the Tugen is naturally divided into three zones, namely: Mosop (the highlands), Soin (the lowland plains) and Kurget (the area between the highlands and the lowlands).

Housing: In Tugen society, several kapish (households) formed a homestead. A household was each wife’s individual house with her children and property. A homestead was a husband’s house and his wives’ houses, the husband’s house being the centre of the homestead.

Economic activities: The Tugen are cattle keepers. Cows occupy a central part in their cultural lives, as food (meat and milk), and currency, as dowry.

Language: Nandi. Alternate names: Naandi, Cemual. Nandi is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Nandi-Markweta, Nandi.

Origins of the community: The ancestors of the present Nandi and Kipsigis migrated from the Mt Elgon concentration area through the uninhabited northern Nyanza forests north of Winam Gulf where they settled around Kamoin salt lick. The Bangomek people who were part of this migration remained on the Kavujai hills while some other groups remained at resting places on the way south-east where they were annihilated or absorbed by Abaluyia groups. Some Kalenjin groups, however, continued their southward migration. The main body left the Winam Gulf area of Lake Victoria and ascended the Kakamega escarpment where the section that eventually became the Nyang’ori (Terik) travelled further north-east, accompanied by the founders of the Nandi pororosiek of Kapsile and Kabianga.

The section that became the Nandi returned to the plains in the area around Nyoiywai, and then climbed the escarpment to settle at Chemngal and Chebilat. These settlements were established by an Elgony (Kony) named Kakipoch after whom the oldest Nandi pororiet (a pororiet consisted of a number of kokwet- organised land units of 20 to 100 homesteads- put together and formed a fighting unit) is eponymously named.

Another proto-Nandi contingent migrated to the east and wandered about between the Kamasia hills and Lake Baringo and as far as Rumuruti to the east before settling around Lake Nakuru. Here they later encountered the Sigilai Maasai who pushed them back to the Kamasia hills and Elgeyo.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Nandi number 949,835.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Nandi settled in Rift Valley Province’s Uasin Gishu district, and Nandi district.

The Nandi live in Nandi County, Uasin-Gishu County, Trans-Nzoia County, Nakuru County and parts of Narok County.

The land of the Nandi ethnic group is divided into six “counties” (emet): Wareng in the north, Masop in the east, Soiin/Pelkut in the south, Aldai and Chesumei in the west, and Em-gwen in the centre.

The Nandi-inhabited plateau extends from Mau (the western wall of the Rift Valley) to the Nyanza plains. The Nandi also occupy areas below the South escarpment in the middle and lower Nyando Plain at the foot of the west escarpment. The Southern and Western limits of the Nandi Plateau are well defined by granite escarpments rising steeply from the plains below. The South escarpment which towers 2,000 feet (609.6m) extends eastwards from the south-west corner of Nandi until it merges with the Tinderet and Mau ranges. Its western counterpart rising about 1,200feet (365.76) above the North Nyanza plain, stretches in an unbroken line from the Yala Valley to Broderick Falls and then continues northwards to join the Elgon Masaif 14,000feet (4,267.2m). The Plateau normally enjoys ample and well distributed rainfall, with a wet season extending from March to October.

Housing: The houses of the Nandi, like those of the Luo and the Luhya, are scattered across their fields and meadows in small clusters of buildings. They are round in shape, with sloping cone-shaped roofs of thatch with overhanging eaves.

Posts are first dug into the ground 20 to 30cm apart. Thinner horizontal pieces of lighter material are fixed across the uprights, both inside and out. The roof is framed in lighter material.

The spaces between the uprights and the cross pieces are packed with clay. The walls are then plastered, inside out, with a mixture of clay and cow dung (the straw in dung binding the mixture together). Lime is sometimes added to the plaster to stabilise it, and decorative patterns may be applied to the outside of the house.

The roof is thatched with grass or reeds, depending on what is available. There are no chimneys, and smoke simply finds its way out through the thatch. Thatching is in most cases a strictly utilitarian exercise, to shelter the occupants from the sun and the rain with no attempt at decoration.

There are doorways front and back. Today, doors are made from sawn timber, but in the old days doors were made of wickerwork. The walls of the house are to be resurfaced every year and the floors touched up every month. They are smeared with cow dung to cut down on dust and the resultant infections from the insects that hide there.

Economic activities: Before British colonization of Kenya, the Nandi were sedentary cattle herders, who sometimes practised agriculture.

Nandi Hills has a cool and wet climate with two rain seasons during the equinoxes. Temperatures vary between 18°C and 24°C which coupled with rich volcanic soils make the area ideal for growing tea.

The Nandi’s major crops are millet, corn (maize), sweet potatoes and yams. Cattle serve as food and are offered as bride-price, and hold great ritual significance. Trade

Cycles of life

Initiation: Traditionally, the Nandi practised circumcision of both sexes, although female circumcision is fast fading as a rite of initiation into adulthood. Boys’ circumcision festivals took place about every seven-and-a-half years. Boys circumcised at the same time are considered to belong to the same age-set; which were given names from a limited fixed cycle. Girls’ circumcision, excising the clitoris, took place in preparation for marriage.

Language: Okiek. Alternate names: Akie, Akiek, Kinare, “Ndorobo”, Ogiek.

Okiek is a member of the macro-language Kalenjin.

Ogiek/Okiek family

The Ogiek peoples are scattered groups of hunter-gatherers in Southern Kenya and Northern Tanzania.

The Okiek, sometimes called the Ogiek or Akiek (although the term Akiek sometimes refers to a distinct subgroup), are an ethnic and linguistic group based in north-western Tanzania, Southern Kenya (in the Mau Forest), and Western Kenya (in the Mount Elgon Forest).

Some “Ndorobo” languages have few remaining speakers. The Akiek of northern Tanzania now speak Maasai. The Akiek of Kinare in Kenya now speak Gikuyu. “Ndorobo” is a derogatory term for several hunter or forest groups, not linguistically related (El Molo, Yaaku, Okiek, Omotik, Aasáx).

The name Dorobo is derived from a Maasai name il torobo which means a “poor person who has no cattle and has to live on hunting and gathering”.

The majority of the Ogiek speak a Kalenjin-related dialect as their domestic language. Most local groups also live near one of the Kalenjin tribes such as the Kipsigis, the Nandi, the Tugen and the Marakwet, and their Kalenjin dialect will tend to be more similar to that of the neighbouring tribe. Those who live in close proximity to the Maasai in Mukogodo and Narok speak Maasai dialects and not Kalenjin languages but they claim to be of the same historic origins as the Kalenjin-speaking Ogiek.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Southern, Kalenjin, Okiek.

Origins of the community: The Ogiek are believed to be the first people to settle in Eastern Africa and were found inhabiting all Kenyan forest before 1800AD. Due to domination and assimilation, the community is slowly becoming extinct with the 1989 figures showing about 20,000 countrywide. The Ogiek are the last remaining forest dwellers and the most marginalised of all indigenous peoples and minorities in Kenya.

The Ogiek community is believed to have occupied the coastal regions of East Africa as early as 1000 AD. They moved from these areas following attacks by slave traders and other migrating communities. This was the Ogiek’s first dispersal. It saw one group moving into Tanzania where they settled among the Hadzabe and Maasai tribes. This group has been assimilated by the Maasai and now speaks a dialect that is very close to Maasai. A second group moved to the plains of Laikipia bordering Mount Kenya Forest from where they dispersed to various locations in northern, central and western Kenya.

By the turn of the century, the Ogiek were to be found in Mount Elgon, Cherangany, Koibatek and Nandi, as well as the Mau Forest region, which straddles Nakuru, Narok, Kericho and Bomet districts in the Rift Valley Province of Kenya. One group moved from Laikipia and settled in Samburu, Northern Kenya.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Ogiek number 78,691.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Ogiek settled in Rift Valley Province’s Nakuru district, East Mau Escarpment; Sogoo in Mau Forest south between Amala and Ewas Ng’iro rivers near Nosogami stream. Also in Tanzania.

The western Mau Escarpment where Kaplelach, Kipchornwonek, and several other Okiek groups live is a forested slope, roughly 66km long, rising in altitude from 1800 to 2800m. Okiek recognise five altitudinally related ecological zones, ranging from open bush forest below 2100m (soyua) to high, dense bamboo forest between 2400 and 2600m (sisiyuet), each zone is distinguished by its most common plant and animal species. Zones have different honey-producing species and honey seasons which have determined Okiek patterns of mobility.

Economic activities: The Ogiek are a hunter-gatherer community of forest dwellers who depended on Mau Forest for subsistence and shelter in the early part of the 20th century. The community divided the forest among their clans using natural features like valleys, rivers and hills as boundaries. The Ogiek depended on the forest for their livelihood. Collection of wild fruits, hunting, honey harvesting were a daily routine.

While meat for the Mau Okiek comprises 75% of their diet, honey (comprising but 15%) is the primary motivation for forest exploitation. There is a striking lack of wild vegetables in the Okiek diet, and it is only children who eat significant amounts of berries and roots.

The animals hunted once included bushbuck, buffalo, elephant, duiker, hyrax, bongo, and giant forest hog. They hunted with dogs, bows and arrows, spears, and clubs, using poison for buffalo and elephant. Men also set traps. Unlike many other hunter-gatherers, Okiek gathered little plant food; they relied on a diet of meat and honey, supplemented by traded grains. In the late 1930s and 1940s Kipchornwonek clan planted small millet gardens; and later the Kaplelach planted maize. Over the next twenty years, however, agriculture became more important. Okiek began to settle more permanently in mid-altitude forest and keep their few domestic animals at home.

The Ogiek are self-sufficient in forest products (wild fruits and roots, game hunting, honey) except for small amounts of iron for making into arrowheads, spears and knives. Trade

Cycles of life Initiation: Initiation was performed around age fifteen, separately for boys and girls. The Ogiek have age-set systems similar to those of the Maasai or the Kalenjin Ipinda. Their initiation ceremonies show superficial resemblance to both Kalenjin and Maasai initiation ceremonies and their initiated young men (muranik) act as the community police against feuding between lineages, and first line defence against attacks and raids by other local groups or tribes. The age-set system also acts as the basis for peer group relations among the men who grow up together as friends, sharing activities in hunting, honey collecting, raiding, dancing and socialising.

Death: Major Okiek ceremonies celebrate stages of social maturation: a head-shaving ceremony where a child receives a new name; an ear-piercing ceremony at age twelve to fourteen (now rarely practised); and initiation into adulthood.